UPDATE: EBLA, AN EVALUATION OF DAMAGE

U. S. DEPT. COOPERATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: S-IZ-100-17-CA021

BY By Kyra Kaercher, Susan Penacho, Katherine Burge, Jamie O’Connell, and Marina Gabriel

* This report is based on research conducted by the “Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative,” funded by the US Department of State. Monthly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change.

Ebla (Tell Mardikh) is located 55 km southwest of Aleppo in Idlib Governorate. Occupied from the Early Bronze Age (ca. 3500 BCE) until the 7th century CE, the site consists of a central high mound/acropolis surrounded by a lower mound comprising the Bronze Age lower town, which is in turn encircled by the remains of a large Middle Bronze Age earth, a stone fortification wall, and a rampart with four gates. The site was excavated by the Italian Archaeological Expedition of the University La Sapienza under the direction of Paolo Matthiae from 1964 until the onset of the Syrian Civil War in 2011 [1]. ��Since 2011, the site has been subjected to illicit digging and looting. The site is well-known locally and internationally due to its long history of excavation and publication of finds. Artifacts recovered from the palaces located on the site include furniture and composite statues inlaid with precious stones, while the royal tombs have yielded jewelry and other precious grave goods. A large corpus of cuneiform tablets found within the Early Bronze Age Royal Palace (Palace G) constitutes one of the oldest archives and libraries ever found. Ebla is moreover historically significant as the capital of an early Syrian centralized state, which is considered by some as constituting one of the earliest empires [2].

Ebla became an urbanized center in ca. 3000-2400 BCE, but truly began to flourish as a regional power in ca. 2400-2300 BCE [3]. ��During this period, the Early Bronze Age Royal Palace (Palace G) was built over the western slope of the acropolis. Excavations in the palace revealed mudbrick walls preserved to a height of seven meters and a number of precious raw materials and finely crafted finished pieces, some of which were very similar to the elite objet d’art found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. Important cuneiform archives were also found in situ on collapsed shelves in a number of rooms in the palace, totaling more than 18,000 tablets dated to around 2350 BCE and written in Sumerian and Eblaite [4]. ��At this time, Ebla appears to have established political and military dominance over neighboring Syrian city-states, all of whom are mentioned in the archives, gaining control of an area roughly half the size of modern Syria [5].

The acropolis of Ebla pre-war showing the Royal Palace (Palace G) and Archives in white (Photo courtesy of Kyra Kaercher; June 2010)

The Middle Bronze Age Royal Palace (Palace E) was built on the newly fortified acropolis, and a temple to Ishtar was constructed over the earlier Temple D [6]. ��Also built to the northeast of the acropolis was The Temple of Shamash (Temple N), and to the northwest, a second Ishtar Temple (Temple P2) [7]. ��The Vizier Palace was built to the south of the acropolis, while the Crown Prince’s Palace (Palace Q) was constructed to the west; the Temple of Resheph (Temple B1) and the Dead Kings’ Sanctuary (B2) were erected in between [8].

Ishtar’s sacred area and temple (Photo courtesy of Kyra Kaercher; June 2009)

The excavated Middle Bronze Age Palace (Photo courtesy of Kyra Kaercher; June 2010)

Dead Kings sanctuary and Resheph Temple pre-War (Photo courtesy of Kyra Kaercher; June 2010)

The royal necropolis for this period was discovered beneath Palace Q; it contains many hypogea, formed from natural caves in the bedrock of the palace’s foundation and dating to the 19th and 18th centuries BCE. Three have been excavated and were found to contain precious jewelry and funerary objects, some of which were imported from Egypt [9]. ��This new kingdom was founded by an Amorite dynasty and served as vassal to the kingdom of Yamhad until the city’s final destruction ca. 1600 BCE by the Hittite king Mursili I [10]. ��Ebla never recovered from the Hittite destruction, though small occupations continued to appear at the site (Mardikh IV, V, VII), until its final abandonment in the 7th-century CE [11].

The Acropolis at Ebla prior to the conflict (ASOR CHI/DigitalGlobe NextView License; December 16, 2008)

From the start of the Syrian conflict, opposition groups began forming in Idlib Governorate. From late January to early February 2012, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) began to capture territory in Idlib Governorate. ��In September 2014, the US-led coalition began conducting airstrikes against Al Nusra Front targets (known then as the Khorasan Group and later as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) in Idlib Governorate. In November 2014, Al Nusra Front began targeting other opposition groups in Idlib, accusing some of collaborating with western forces. Al Nusra Front captured the city of Idlib in April 2015. By June 2015, the organization had reportedly control of over 90% of Idlib Governorate, along with other Islamist opposition groups, including the Fattah Army Coalition. ISIS also held areas of Idlib from August 2011 until January 2014, before being forced out by opposition forces. At present, opposition forces led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (formerly Al Nusra Front) continue to maintain control over the majority of the region. As a result, between late-September 2015 and mid-2017, Russian and SARG forces carried out intensive aerial bombardment over Idlib Governorate. In 2017, much of Idlib Governorate was in a so-called “de-escalation zones,” brokered by Russia, Iran, and Turkey, and aerial bombardment over the area largely ceased. However, 2018 brought renewed aerial bombardment over the area by both Russian and Syrian forces as the Syrian regime renewed it offensive against opposition forces. Aerial bombardment ��over much of Idlib Governorate on a near daily basis.

Damage to Ebla

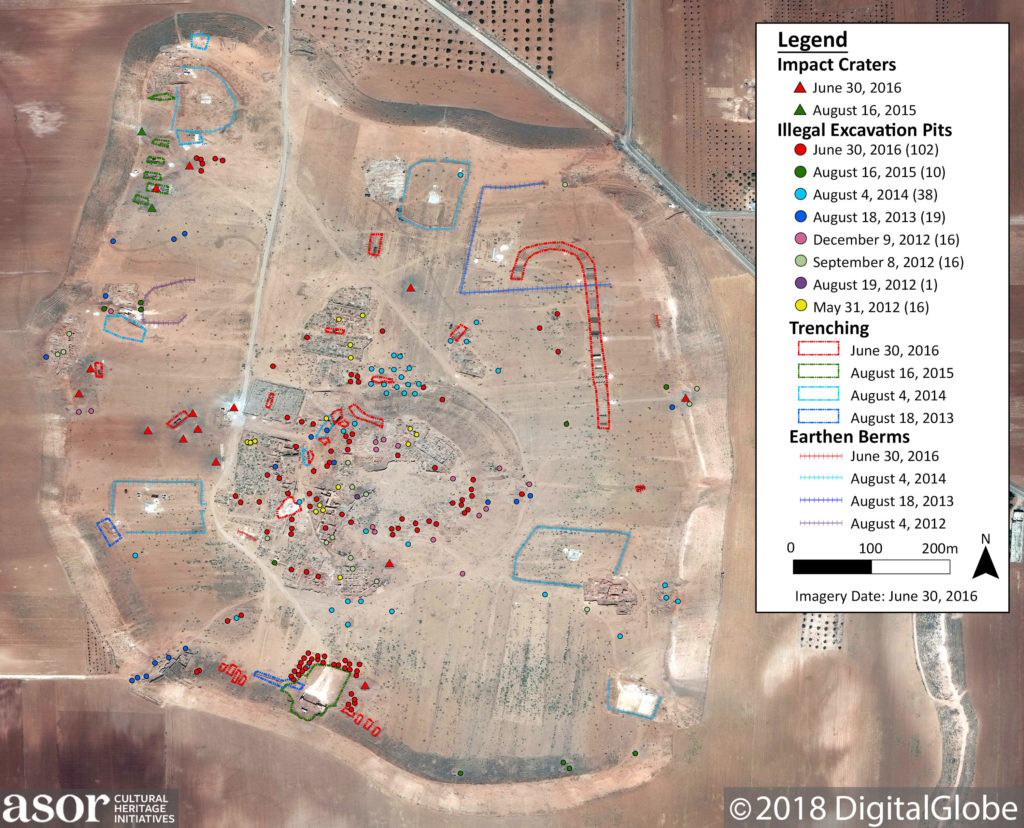

Annotated satellite image of damage to Ebla, separated by date first visible. Not all the looting pits are noted as they were not clear in available images (ASOR CHI/DigitalGlobe NextView License; June 30, 2016)

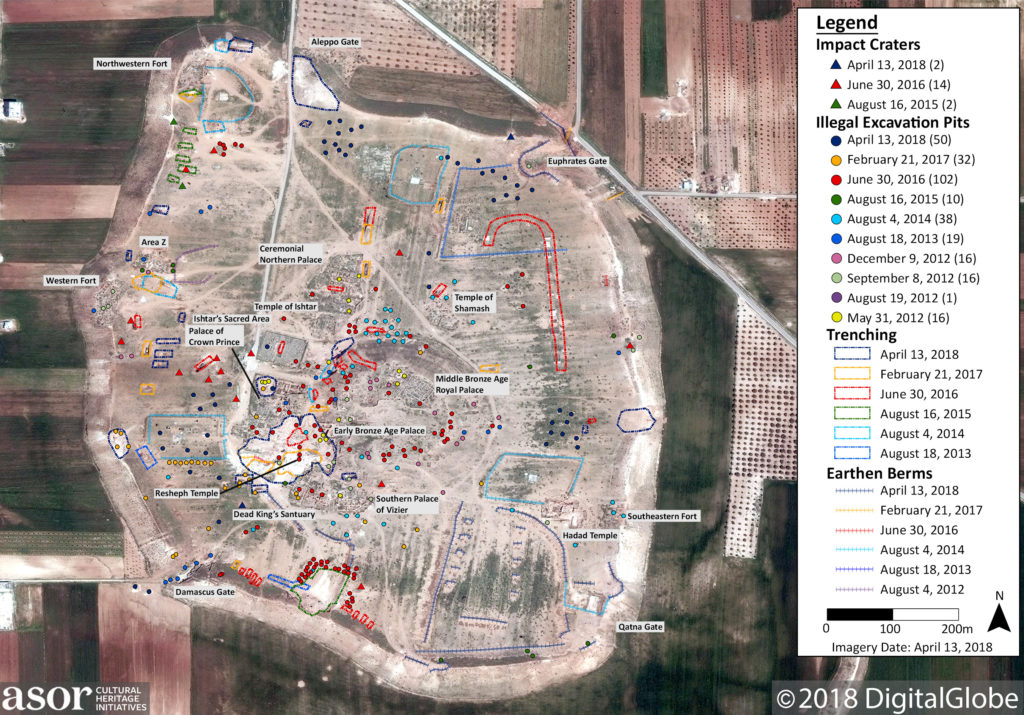

ASOR CHI analysis of ongoing damage to Ebla through April 13, 2018 (ASOR CHI/DigitalGlobe NextView License; April 13, 2018)

Illegal Excavation/Vandalism

In April 2012, the Association for the Protection of Syrian Archaeology (APSA) that looting was occuring at the site of Ebla. DigitalGlobe satellite images from May 31, 2012 show looting pits in previously excavated areas on the Acropolis. The DGAM that illegal excavations had occurred at the Early Bronze Age Royal Palace and Archives, and the Middle Bronze Age Royal Palace on the Acropolis, as well as areas south and southeast of the Acropolis.

In November 2013, the DGAM reported that they met with officials and locals at Ebla to discuss ways to combat the looting. However, looting at the site with the use of heavy machinery. DigitalGlobe satellite imagery from August 18, 2013 shows increased looting on the Acropolis and the Damascus Gate. On November 12, 2013 DGAM representatives again visited the site and published photographs confirming reports of looting on the Acropolis and on the northwest slope below the Acropolis area.

The Early Bronze Age Royal Palace at Ebla pre-conflict (Photo courtesy of Kyra Kaercher; June 2010)

Vandalism and looting at Ebla (DGAM; Published December 11, 2013)

The Early Bronze Age Royal Palace showing damage due to the elements, vandalism, and illegal excavation (DGAM; June 15, 2014)

Looting pit near the eastern fortification wall on the Acropolis (DGAM; November 12, 2013)

In February 2014, the DGAM that the looting had stopped and Ebla was now occupied by an unnamed “armed group.” The date of the incident would suggest that Syrian opposition forces, possibly including elements of then-called Al Nusra Front, controlled the site at this time. DGAM officials the site in June 2014 and published photographs showing numerous looting pits, including some that were “down to the foundations of the walls,” as well as evidence of the use of heavy machinery (ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 14-0101 in ). UNITAR published a report that identified looting between 2008 and 2014, resulting in severe damage and destruction at the site, including in Area CC, Area F, the Great Temple of Ishtar, the Dead Kings’ Sanctuary, the Qatna Gate, the Temple of Resheph, the South-Eastern Fort, and the site museum, as well as moderate or possible damage elsewhere on the site.

Evidence of looting and heavy machinery on the Acropolis (DGAM; June 14, 2014)

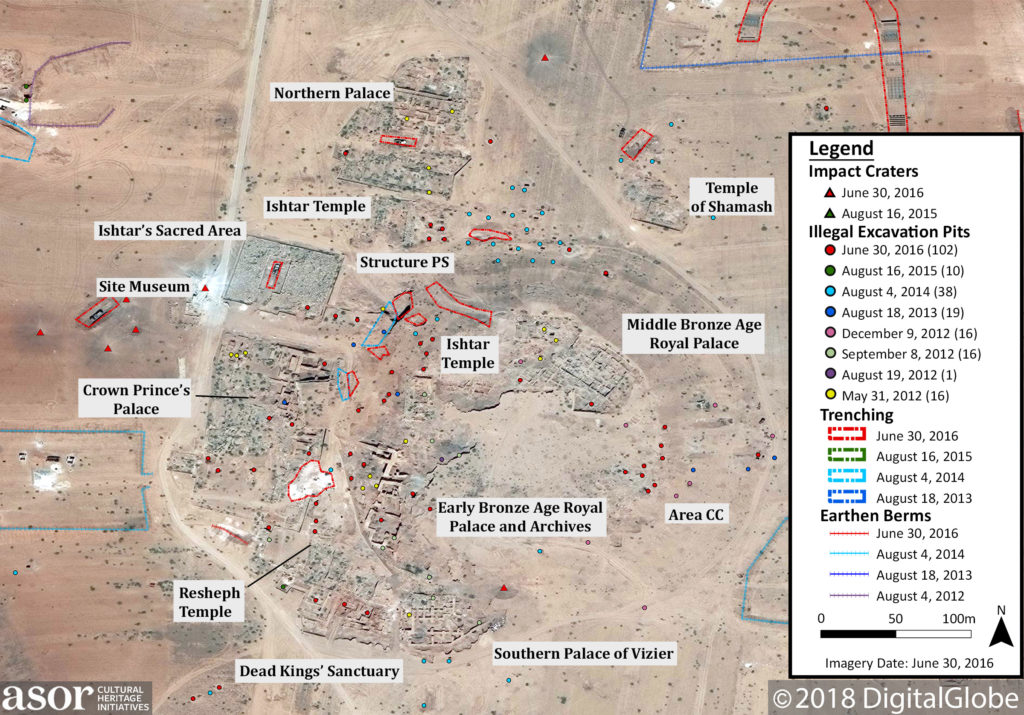

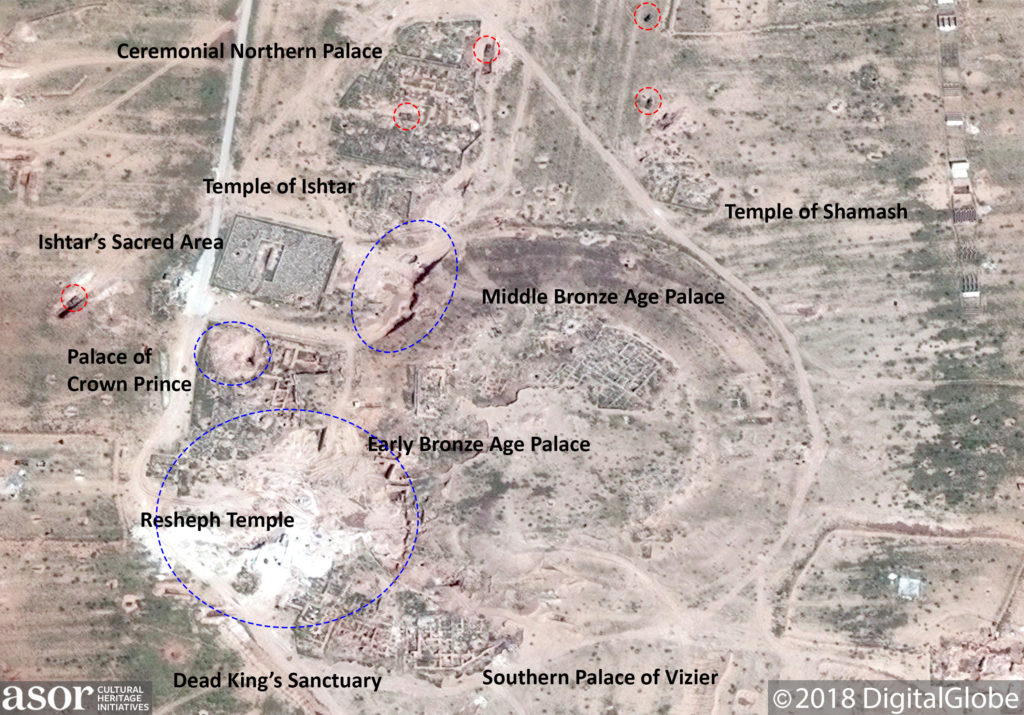

On May 31, 2015 an ASOR CHI in-country source visited Ebla and reported seeing a number of illegal, unregulated excavations. They also saw unspecified damage at several areas of the site, especially in the Early Bronze Age Royal Library, the Temple of Shamash, the Temple of Ishtar, and the Early Bronze Age Royal Palace. New looting pits and expansion of previously excavated areas were visible, primarily around the Northwestern Fort. Many of the previously excavated areas looked to have degraded, with vegetation and soil infilling over time. Based on DigitalGlobe satellite imagery between August 16, 2015 and June 30, 2016 additional looting occured at Ebla and focused mainly on the northeastern side of the Acropolis. Area CC is no longer visible and looting pits cover the area where it once was. Structure PS has been destroyed using heavy machinery. New bulldozer tracks are visible up the acropolis on the western side of the Middle Bronze Age Palace. Excavations have also taken place on the southeastern edge of the Palace of the Crown Prince.

Annotated satellite image of damage to the Acropolis of Ebla, separated by date first visible. Not all the looting pits are noted as they were not clear in available images (ASOR CHI/DigitalGlobe NextView License; June 30, 2016)

Since June 30, 2016 illegal excavations have increased, specifically on the southwestern side of the acropolis near the Resheph Temple and Early Bronze Age Royal Palace. Some of these structures’ walls were to a depth of seven feet, but all have been re-plastered and in some cases reconstructed. Between February 21, 2017 and April 13, 2018 the remains of the Resheph Temple and the Early Bronze Age Royal Palace disappeared. In addition to these illegal excavations, there was an expansion of the bulldozing at the base of the acropolis mound on the northwestern corner close to the Middle Bronze Age Royal Palace. The northwestern corner of the Palace of the Crown Prince was also disturbed by illegal excavations. Bulldozing can be seen around the northern corner of the mound near the Aleppo Gate.

Severe damage to Ebla due to ongoing illegal excavations (outlined in blue) (DigitalGlobe NextView License; April 13, 2018)

Military Construction

Between June 27, 2012 and August 4, 2012 a military outpost was erected on the western side of the site. By September 8, 2012 an earthen berm was constructed around these structures. An August 4, 2014 DigitalGlobe satellite image shows an increased number of earthen berms set up around the site. By August 16, 2015 Ebla was occupied by an opposition force and new constructions (including trenching into the mound to fortify positions) were built at the northwest corner and the southern edge of the site. By 2016, the military force occupying the site dug trenches into the mound to create fortified positions for armored vehicles, some of which can be seen in place on satellite imagery. Some of these vehicles are parked on archaeological material, including the Northern Palace and Ishtar’s Sacred Area. A possible military training ground also appears on the western side of the site, as well as new looting pits, primarily on the Acropolis and the southern edge of the mound. Between February 21, 2017 and April 13, 2018 new earthworks were constructed on the southeastern area of the mound and in the northeastern corner near the Euphrates Gate.

Earthen berms constructed at Ebla (DigitalGlobe NextView License; August 4, 2014)

Military vehicles (red outlines) and a military training course and earthen berms (red arrows) on the mound of Ebla in addition to the ongoing illegal excavations (outlined in blue) (DigitalGlobe NextView License; February 21, 2017)

Airstrikes

On October 1, 2015, a Russian Air Force bombing campaign reportedly the sites of Shinshara, Serjilla, and Ebla. On November 18, 2015 an ASOR CHI source visited Ebla to confirm damage from this incident and another airstrike that occurred the week of November 9, 2015 (ASOR CHI Incident Report 15-0137 in ��and Incident Report 15-0150 in ). The ASOR CHI in-country source confirmed that Ebla was in fact hit by these strikes.

The Day After Heritage Protection Initiative (TDA-HPI) produced a report which indicates that Russian airstrikes struck the eastern side of the acropolis, causing damage and leaving a hole in the acropolis slope. Images in the TDA-HPI report detail damage to the acropolis, as well as damage to the eastern slope. On February 25, 2016 the Russian Air Force reportedly carried out five air strikes targeting the eastern side of Ebla. Another five air strikes were out the next day, causing severe damage to the western and southern sides of the archeological site. DigitalGlobe satellite imagery confirms multiple impact craters on the mound, often located close to a military trench or vehicle. In the image from June 30, 2016 impact craters surround a vehicle trench where the vehicle is still visible. The nearby site museum was also struck during this time.

Airstrike crater at Ebla (TDA-HPI; November 13, 2015)

Remains of a rocket found near crater (TDA-HPI; November 13, 2015)

An airstrike crater at Ebla (TDA-HPI; March 2, 2016)

An airstrike crater at Ebla (TDA-HPI; March 2, 2016)

Remains of a weapon, possibly a mortar (TDA-HPI; March 2, 2016)

Conclusion

Ebla has been severely damaged during the conflict. Illegal excavations have damaged the integrity of exposed architecture on the site, causing it to collapse, and these illegal excavations are ongoing. The construction of military outposts and training grounds by Syrian opposition forces have led to Ebla being targeted by airstrikes and bombing campaigns for the past three years. As of the release of this report, the site is still controlled by opposition groups. Threats continue at the site including illegal excavation, theft, vandalism, illegal construction of military outposts, and airstrikes/bombing campaigns in the region.

[1]��Matthiae, Paolo (2013). “A Long Journey. Fifty Years of Research on the Bronze Age at Tell Mardikh/Ebla”. In Matthiae, Paolo; Marchetti, Nicolò. Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. Left Coast Press, p. 37.

[2]��Liverani, Mario (2009). “Imperialism”. In Pollock, Susan; Bernbeck, Reinhard. Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons, p. 228.

[3]��Matthiae (2013), p. 37.

[4]��Akkermans, P. M., & Schwartz, G. M. (2003). The archaeology of Syria: from complex hunter-gatherers to early urban societies (c. 16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press, pp. 235, 240.

[5]��Idem, p. 239.

[6]��Idem, pp. 300-301.

[7]��Idem, p. 301.

[8]��Idem, p. 301.

[9]��Akkermans & Schwartz (2003), pp. 299-300.

[10]��Matthiae (2013), p. 106.

[11]��Pettinato, Giovanni (1991). Ebla, a new look at history. Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 16.